Eli Lehrer made a series of assertions in an opinion piece, “robots are not a big deal,” published in the Washington Examiner on September 4th. His fairly standard set of claims, however, cannot withstand an analysis based on either broad historical data or a detailed analysis of current economic trends.

Lehrer begins by pointing out that in 1800 “weavers feared the steam loom” and implies that those who are concerned about the impact of robotics on the modern workforce are simply modern Luddites.

That view assumes that the world today is as it was in 1800, that the Industrial Age never happened. It is not. In but one example, few people had more clothes than they could wear at one time in 1800 and peoples’ desire for more and better clothing was a huge reservoir of pent-up demand. Such reservoirs of demand no longer exist in developed countries where societies are drowning in excess goods and services and there is a never ending push to expand consumer demand; the steam loom analogy, while seductive, is inaccurate.

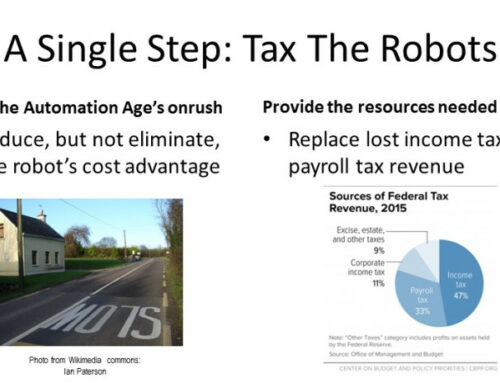

The difference between “then and now” runs far deeper, however. The Industrial Revolution, with its substitution of mechanical power for animal power and simple automation (which Mr. Lehrer appears to equate to Artificial Intelligence or AI) created a vast set of skilled and semi-skilled jobs that were available to people in the middle of the talent and education demographic to create the Middle Class as we know it today. Those middle of the spectrum jobs are the ones attacked by advanced automated systems. The result is the reported “hollowing out” of the middle of the income spectrum. While new jobs are being created by robotics and AI, they require skills such as writing code and performing research that do not support the middle of the population in the same way or at the same level.

Putting it another way, a bulldozer operator mining coal is unlikely to easily become a robotics technician because of the training and talent gaps involved; the “I’m interested in this” gap is enormous.

Within that perspective, we examine four specific assertions in Mr. Lehrer’s essay.

Assertion one: “There is no new technology now or on the horizon that will allow the same amount of economic production to occur with vastly fewer people.” To support that assertion, Mr. Lehrer continues “The Bureau of Labor Statistics has found that average productivity growth since the Great Recession ended in 2007 has been the slowest of any long economic expansion of the post-World War II era, even as technological progress marched on.”

The justification for the assertion, poor recent productivity growth, has nothing to do with future productivity growth. Productivity growth is driven by investment in technology, not technology itself. The Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis indicates that investment has lagged since the end of the Great Recession. This appears to be a byproduct of slow wage growth limiting the investment return provided by investments in technology. Companies have spent $4.7 trillion on stock buybacks over the last decade rather than invest that money in enhancing productivity according to Kiplinger.

It is little wonder that productivity growth has lagged over that period.

Meanwhile, technologies that can eliminate millions of jobs are being perfected and will be ready when wages rise sufficiently to make their implementation, i.e., investment in them, profitable. For example, the self-driving vehicle imperils the jobs of 3.5 million over the road truck drivers as well as taxi drivers and pizza delivery people.

Assertion two: “… entire categories of jobs have never vanished overnight …” based on coal as an example where “… the decline did not occur suddenly …” and “In 1919, about 700,000 Americans, nearly 2% of the labor force, earned their living mining coal. Today, about 50,000 people work in coal, about 3/100ths of 1% of the labor force …” Lehrer then continues “The same pattern repeats itself across other declining industries …”

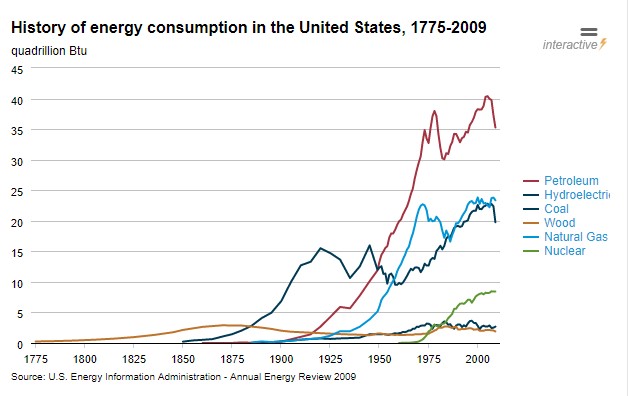

Coal may look like a declining industry at first glance, but the reality is more complex. Its use as an energy source in the United States increased rapidly from about 1960 to the turn of the 21st Century as shown in the U.S. Energy Information Agency (EIA) graphic. Importantly, however, domestic use of coal as an energy source is only one part of the industry as coal exports for coking and energy grew from less than 40 million metric tons in 2002 to more than 100 million metric tons in 2018 according to EIA data.

Coal may look like a declining industry at first glance, but the reality is more complex. Its use as an energy source in the United States increased rapidly from about 1960 to the turn of the 21st Century as shown in the U.S. Energy Information Agency (EIA) graphic. Importantly, however, domestic use of coal as an energy source is only one part of the industry as coal exports for coking and energy grew from less than 40 million metric tons in 2002 to more than 100 million metric tons in 2018 according to EIA data.

If coal is not an industry in severe decline, how is the assertion that the 93% decline in employment “did not occur suddenly” justified? Lehrer provides no data for the critical 60 years from 1959 to 2019.

Assertion three: “The jobs that are the easiest to automate will always be those that are most repetitive and dull …” That may have been true long ago because the work automated was physical but many jobs that are being automated today are intellectual ones. Lehrer does not appear to understand the nature of AI where simple retraining of a developed AI engine allows the tool to be applied to different complex intellectual tasks. IBM’s Watson is already being used in medicine (cancer research, patient care, DNA analysis, diagnoses, and X-ray and MRI interpretation), finance (financial guidance and risk management), and law (case law research for legal precedents). High-skill, non-repetitive jobs are being eliminated as a result.

Assertion four: “The need for vastly fewer people on farms (about 2% of the labor force today compared with over a third a century ago) hasn’t destroyed jobs associated with food, but instead helped to create millions of new jobs in restaurants, food processing, and related industries.” Mr. Lehrer provides no rationale for how unemployed farm workers created new jobs because none is possible. How do unemployed farm workers pay for restaurant meals?

The expansion of the middle class that came with post World War I industrial development and the more recent growth of the service economy created the demand that made those jobs (primarily the 11 million jobs in the restaurant sector in the US) possible.